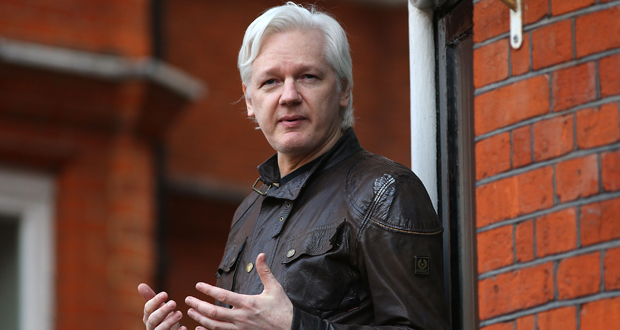

Calling Julian Assange a journalist, or even a whistleblower, is reckless at best and dangerous at worst, according to a Charles Sturt University intelligence and security expert, who says doing so detracts from the important role those who truly deserve such labels play within society.

“Whistleblowers can play an important function in identifying wrongdoing of all kinds, including corruption, abuse of power, human rights issues, etc,” says Associate Professor Patrick Walsh.

“In some ways, they are pressure valves in democracies that allow wrongs to be addressed, that people are not aware of, or people in positions of power are keen to keep secret.

“Assange and WikiLeaks called themselves whistleblowers and so did many of their followers.

“But I think there is a danger in calling people like Assange and even [Edward] Snowden whistleblowers because their release of classified sensitive information was generally indiscriminate, without concern for the potential damage to national security or the rights to privacy of innocent people that are caught up in their activities/leaks.”

Walsh argues that the arrest of the WikiLeaks founder at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London earlier this month provides an opportunity for debate around the charges now against him, and whether or not he was using the promotion of freedom of speech for his own self-promotion, in ways that might damage democratic institutions.

“The UK has charged Assange with effectively skipping bail after he failed to present at a court hearing on extradition charges by Sweden based on alleged sexual assault charges in 2012,” Walsh says.

“More significantly, the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia has charged him with a single charge of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion.

“They allege that he assisted Chelsea Manning [then Private Bradley Manning] to break a password to a classified US government computer.”

This breach resulted in the October 2010 release by WikiLeaks of some 391,832 classified documents on its website, related to US military forces in Iraq during the period January 2004 to December 2009.

Another batch of some 250,000 US State Department messages (cables) sent by US embassies abroad was also released in November 2010.

Walsh says his arrest is a good time to reflect on Assange and WikiLeaks, posing the question: Was Assange and WikiLeaks ever, as promoted, a whistleblowing or journalistic agency interested only in free speech and government transparency?

“Assange released a lot of sensitive material from the Pentagon, which included names of people US intel agencies were using as sources or who were in some capacity working for the US military.

“This puts the lives of these people and their families at great risk. It makes it less likely that in the future sources in conflict zones will want to trust the US and its allies if they feel their personal details will not be protected.

“This can result in our intelligence agencies knowing less about terrorism or other threats on the ground that could be in a position to do harm to our soldiers, or who may be planning attacks in Australia and elsewhere.

“Such leaks also damage general efforts by our intelligence community to collect information about threat actors if leaks reveal collection methods, as in the case of Snowden.

“The intel community is still struggling with the ‘going dark phenomenon’ of various communication platforms post Snowden.”

Despite warnings from his own people about the indiscriminate dumping of the US classified pentagon material on the WikiLeaks website, Walsh says Assange didn’t consider, or seem to care about, the impact this might have on the people included who were innocent.

“This is reckless activity – and not in the tradition of what I think are real whistleblowers, such as Daniel Ellsberg (Pentagon Papers) and Sgt Joe Darby (Abu Ghraib), who were motivated by ethical concerns about the direction of their country in Ellsberg’s case, or human rights abuses in Darby’s case.

“In both these whistleblowing cases, their decision weighed heavily on them. In Ellsberg’s case, he tried to not release information about sensitive ongoing negotiations between the US and North Vietnamese communist government that was seeking a peaceful end to the conflict.

“I think a true whistleblower is driven not by narcissism or ‘how can I get my 15 minutes of fame’, and more by the concern over an abuse of power that needs correcting.

“Their motives are more selfless than Assange’s motivation, which was fundamentally about doing as much damage to US interests worldwide, rather than specific policy concerns.

“I also think if Assange was a true whistleblower motivated only – as he claimed – by transparency and free speech, then why was there never anything much published on their page about abuses of power in authoritarian states, where even the idea of leaking classified information would result in execution of the person who leaked it?

“If you were interested in a balanced view of keeping all powers honest, why not hack into and release material from Russia or China?”

Walsh says the conversation sparked by Assange’s arrest is an important one, within Australia and all liberal democracies.

“There is whistleblowing legislation in Australia, but it’s more difficult in the national security intelligence context than, say, exposing police corruption or corporate fraud, because the release of such information – even if the motivations are from an ethical framework – can cause enormous damage to the security of a country.

“This doesn’t mean that whistleblowers don’t have avenues to seek redress in the intelligence community.

“In Australia, we have a parliamentary committee that has oversight of our intel community. We also have the Inspector General for Intelligence and Security (IGIS), which is an independent oversight body that has standing royal commission powers to investigate the operations of agencies in the intelligence community.”

Aside from the associated debate, Walsh says there is very little to be gained from the activities of someone like Assange or even Snowden.

“In the case of Assange, he is at best a hacker, at worst a useful idiot for the Russian state.

“Someone who is just interested in hacking government institutions but doesn’t do it for any real positive reason, or one that can result in a positive result, is of limited value to the pursuit of free speech and transparency.

“Assange and Snowden both influenced a more critical debate now in liberal democratic states about the role of intelligence agencies: secrecy versus transparency and privacy.

“So I suppose advancing this debate has been helpful, but doing it the way Assange and Snowden did it is not the way to ignite this debate.”

In addition to the whistleblower debate, there has also been extensive discussion within the media as to whether Assange should be considered a journalist.

According to Walsh, Assange is no such thing.

“He has a long history of hacking rather than journalism. I do not know if he has any journalism qualifications, but a professional journalist would not just mass-dump unredacted information on their website.

“They would sift through it, remove names of people not relevant to the story to protect their privacy and security. They would seek to critically assess the information first as well – try to value-add to it and contextualise it.

“Assange does none of those things.

“It’s an affront to all those people who go to journalism schools and work tirelessly to produce good journalism in democracies.

“Secondly, Assange and his lawyers are connecting his arrest as a ‘journalist’ to the endangerment of free speech in general, which is hyperbole. Free speech is not in danger because of his arrest.

“Thirdly, I would say he is not a journalist because no ethical or professional journalist would actively conspire with a source to break a secure password on a classified computer to access the information from a source.

“This is not journalism; it’s criminal hacking for which the person involved has a case to answer for.”

Walsh says as a result of Assange and WikiLeaks, intelligence communities may need to consider processes in the future that allow genuine whistleblowers a secure, confidential oversight forum to air their grievances before going to the press in ways that don’t minimise their concerns, yet risk-manage the consequences of their going public.

“Generally, in Australia and other liberal democracies, things can go wrong, abuse can happen, particularly in conflict zones, but most people working in the intel community are honest and ethical.

“But now and in the future, powerful oversight of our intelligence communities will be the best way to pick up abuses, not via the Assanges and Snowdens of the world.”